The first IBM computers were limited in what they could do compared to what we have today. The very first commercial ones used vacuum tubes instead of transistors as the switches for circuits. They were slow, hot, and required a lot of maintenance. A large vacuum tube computer could heat a large building. In the 1960’s transistors were being developed that were much smaller, more reliable, and faster switching than vacuum tubes. The main issues of the day were: transistors were still too large for a computer storage, and generated too much heat. It was not practical to place a large number of transistors close enough together to form a computer memory, so a hybrid system was developed, using tiny powdered iron doughnuts much smaller than the head of a pin. Fast transistors placed outside of the magnetic memory core plane provided enough current (it required two) to flip the magnetic state of one individual doughnut. To see one of the core doughnuts requires a strong magnifying glass or a microscope to really see the structure. Follow this link to see a core storage plane taken from an IBM System 360 computer.

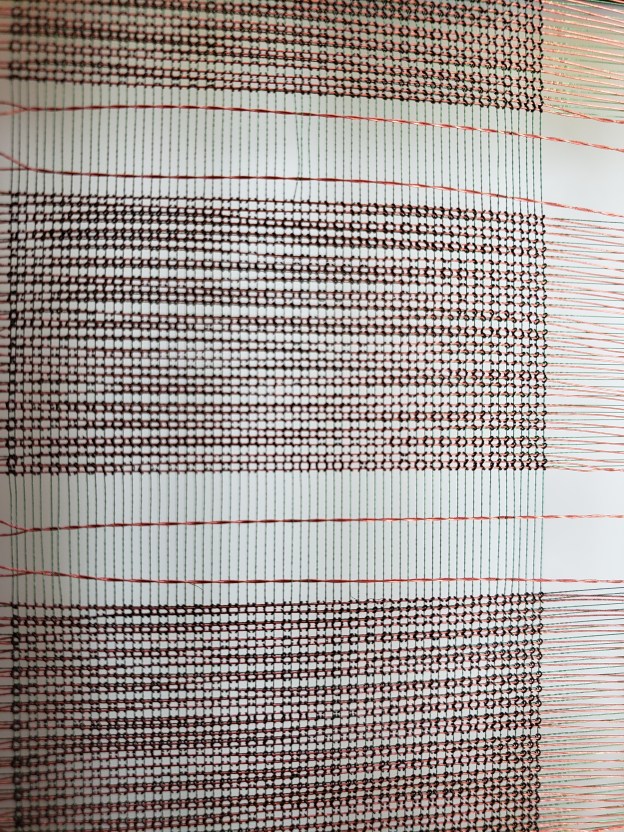

Core Storage

Three tiny wires were hand threaded through each doughnut to form a matrix and transistors connected to the edge of the core array. The powdered iron doughnuts and the three wires formed what was called a core plane. A stack of these core planes formed a core array. Making these core planes was a very intricate, time consuming, and expensive process. The tiny iron doughnuts had to be carefully hand wired by hand under magnification. Two wires (much finer than a human hair) formed a X and Y axis address and a third wire laced through each doughnut acted as a sense/inhibit wire to either sense if a particular doughnut changed its magnetic state from a 0 (off) to a 1 (on), or vice versa. The third wire could also inhibit (prevent) a particular doughnut from changing its state. To change the state of one of the core doughnuts required the current of two transistors to change or flip its on/off state. Because all of the doughnuts had X and Y wires wired through them, the sense/inhibit wire was also used to prevent a particular core position from flipping. If a core flipped its magnetic state with current from an X wire and a Y wire, it caused a pulse to be developed on the sense/inhibit wire, which could be detected. Complex logic circuitry was required to make all of this happen. Data and the computer program was loaded into the memory in locations that were numbered in hexadecimal notation, and located by an X and Y axis. Hexadecimal addressing was used because everything in memory was referred to in bytes, or groups of 8 bits. Hexadecimal addressing is numbering to the base 16, instead of the base 10 we are used to. It consists of 0 to 9 A (10) B (11), C (12), D (13), E (14), F (15).

Operation

When the computer program is running, data is read and manipulated by logic circuits according to the computer program. All of the program and data was located in a parts of the core storage. Circuits would perform mathematical computations and logical manipulations on data located in core storage locations. Data was often loaded into registers for logical operations to be performed, like shifting data, bit by bit, or performing binary arithmetic functions, logical comparisons, and many more. For its time System 360 had a rich instruction set. The operations were usually carried out by reading data out of a core storage location and being placed into a hardware register (which were faster than core storage). The fastest computer instructions were done register to register; the slowest instructions were performed from core storage to core storage. After the computer instruction was complete the changed data was read out of a register back into a core storage location and then the next instruction in the program was executed. Data could then be transferred from core storage to magnetic tape or disk storage, or printed or even punched out into a card deck.

Microcode

Part of the logical computer instructions were carried out by a piece of hardware and code located between the computer’s actual hardware (transistors and diodes), and the program running in the core storage. This code was called Microcode by IBM. Microcode allowed IBM to use less physical circuitry to perform complex instructions, like floating point operations, and IBM could change how a group of circuits functioned in carrying out a particular instruction or operation. Today, most computers and other devices do the same thing and refer to this operation as firmware. Firmware or microcode allows the manufacturer to change how a circuit or device operates and works. They can make changes quickly and inexpensively, with just a download of new firmware, instead of replacing expensive hardware, to add functionality to a device, or to correct a problem.

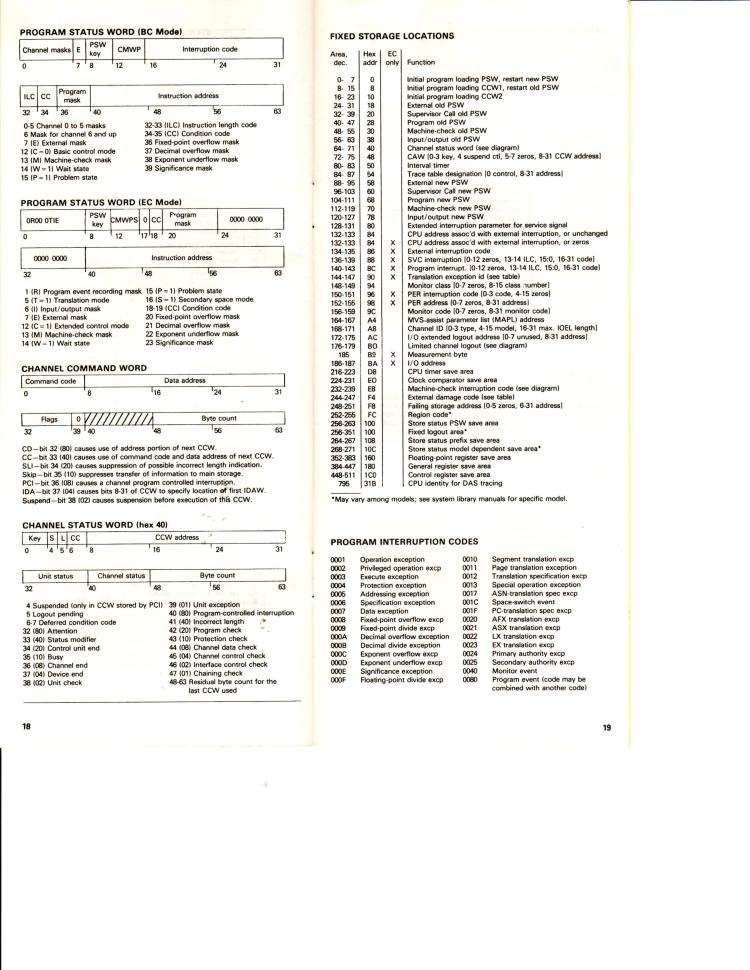

Fixed Storage Locations

IBM hardware had some fixed storage locations that were used to carry out certain program functions. When a program instruction called for reading data from a input or output device, that instruction caused the hardware to interrupt the CPU, branch (go to) a specific low core storage address, and that location held a core storage address of an I/O routine that addressed the particular I/O device, and directed it to read or write.

Programs and data comprised of rectangular holes in punched in cards that were fed by a large card reader into the computer’s core storage. Often large trays of program cards were carried to a card reader to be read into the computer. They were heavy, and once in a while a tray dropped. That was a disaster! It took some time to pick up several thousand punched cards and get them in order again. The first cards in each deck were special ones called JCL – short for Job Control Language. These JCL cards told the computer the name of the program, what input and output devices were required for the execution of the program, where the program or other parts of the program were located (tape drive, card deck, disk drive, etc. and other information critical to the execution of the program. JCL coding could get quite complicated and if it was not exactly correct, the job or program would often fail. One thing to remember about computer programming: Close is not good enough – everything must be exactly correct!

Today’s computers have massive amounts of memory in quantities that were not imagined in the early days. We have gone from kilobytes (thousands) to megabytes (millions) to gigabytes (billions) to terabytes (trillions), petabytes (quadrillion), and beyond. A byte in these early computers was eight core positions, eight bits plus one parity bit defined a byte. Two bytes comprised a computer word in the IBM world. It was thirty-two bits of core storage plus an extra bit for each byte called the parity bit. The parity bit was used by the hardware in an algorithm to make certain each byte in a particular machine was either odd or even. (most were odd parity). A byte was usually the smallest piece of data usually referred to at IBM. Sure, you could manipulate down to the bit level, but we generally spoke in numbers of bytes. If a byte was determined to be ‘out of parity’, the computer would generate a machine check error and the computer would halt or ‘crash‘. In the early days of computers, there were no display devices like there are today; those came along years later. The only way to communicate with the early computers was an IBM typewriter.

If a CPU generated a program check, usually a user programming error or operating system error occurred. A ‘core dump’ was usually printed out. This was a mountain of paper, often two to three feet tall, with all of the hexadecimal (0 to 9, A,B,C,D,E,F) characters of the core storage. We would look at the PSW (program status word), registers (there were 16), the fixed core storage locations, the user program instructions, and the IBM operating system and I/O that were executing at the time of the failure to determine what was going on at the time of the error.

Input & Output Devices

Input/output devices were large card readers and card punches, large magnetic tape drives, and disk drives. Huge printers or disk drives usually provided the output from the computing. Visual displays came along years later. The only way to communicate with these old computers was an electronic typewriter or switches at the console of the computer. The console typewriter was sometimes the Achilles Heel of a million dollar computer. These very expensive computers could be down because the computer operator could not communicate with the computer. The very early operating systems were: OS/MFT and later, OS/MVT.

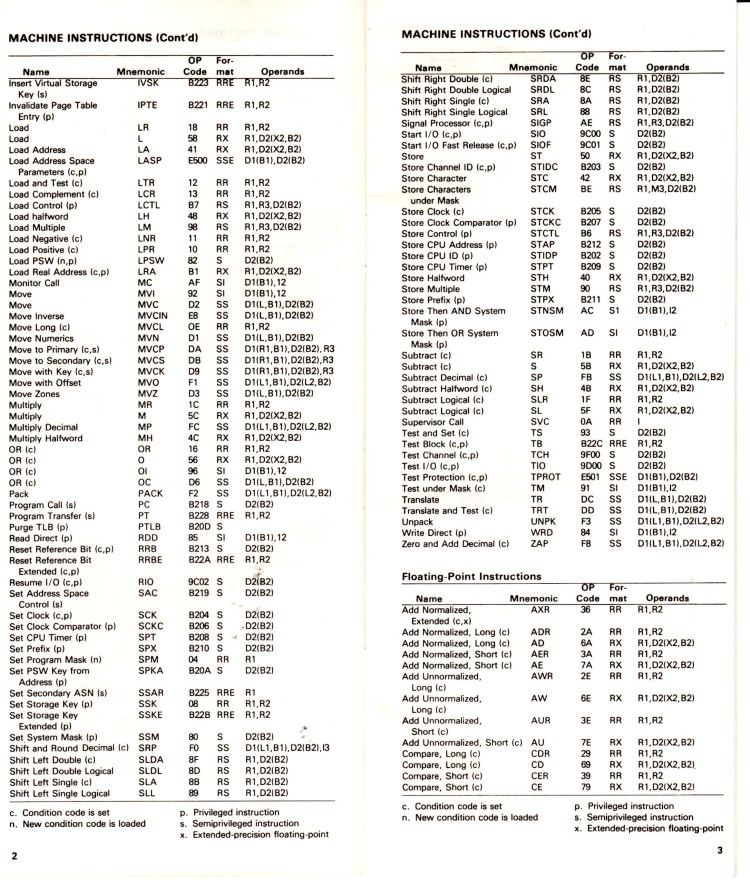

Computer Instruction Set

The first computer programs were written in machine language. It is difficult and time consuming to write a program of any consequence in machine language. One of the first higher language for the IBM mainframes was called BAL (Basic Assembler Language). BAL was almost like writing in machine language, but you did not need to worry about what operating system was doing as you would need to do if you were writing a machine language program. OS MFT or OS MVT would take care of the input and output devices reading and writing data into and out of your program, handle the interrupts, and other housekeeping operations. You could be free to code BALR (Branch and Link Register), Add, subtract, multiply, and divide operations. There were logical compare instructions like CL, CLC, CLI, CLM, and CLCL. Several variations of move instructions were available to move data from register to register or to move data to and from storage locations. Bit masks can be used to compare data. If you look at Intel’s instruction set today, that both Apple and the PC use, they are not that much different to IBM’s original instruction set in the 60’s.

Computer Errors

Program checks were quite common in the early days. Programmers would code a program to access data outside the available memory or into a protected area of the operating system. A program check was issued by the operating system, the program would come to a halt, and the computer operator would issue a core dump command from the console typewriter so the programmer could find out why the error occurred. Sometimes it was a coding error, other times it was an operating system error.

When you see a ‘blue screen of death‘ displayed, on your PC today, it will display the memory locations, data, instructions, and registers associated with the failure. Most home computers today do not have parity checking memory anymore (RAM has become quite reliable), but some more expensive engineering PC’s still have parity checking RAM. Today’s computers and computerized devices are much more reliable than the early ones, and are tested with alpha and beta versions of software and hardware before being released to the general public. Once in a while, something will sneak through the cracks though.

If the early computers seem complicated, they were; computers are even more complicated today, much smaller and faster, yet they work today much the same way as they did yesterday. When I hear advertisements touting “artificial intelligence” today, I get a little up tight. Most of the people who program computers do not know where they came from and how they work internally. There are some people who believe computer programs (software), will someday make the computer become smarter than the machine (hardware) itself, more intelligent than the programmers who programmed it. I don’t think so. Computers still have inputs, an instruction set, a processor or multiple processors, (where the program is parsed and executed), memory, registers (where data manipulation of data takes place), and outputs. The basics haven’t changed.

One Page of 370 Instructions

PSW and Fixed Storage Locations